Part of my job is validating (i.e. testing and confirming) new designs for the website I work on. We A/B test the current page against a new page, and confirm (or otherwise) that the new version is indeed better than what we have now. It's often a last-stop measure before the new design is implemented globally, although it's not always a go/no-go decision.

The new design has gone through various other testing and validation first - a team of qualified user experience designers (UX) and user interface designers (UI) will have decided how they want to improve the current experience. They will have undertaken various trials with their designs, and will have built prototypes that will have been shown to user researchers; one of the key parts of the design process, somewhere near the beginning, is the development of user personas.

A persona in this context is a character that forms a 'typical user', who designers and product teams can keep in mind while they're discussing their new design. They can point to Jane Doe and say, "Jane would like this," or, "Jane would probably click on this, because Jane is an expert user."

I sometimes play Chess in a similar way, when I play solo Chess or when I'm trying to analyze a game I'm playing. I make a move, and then decide what my opponent would play. I did this a lot when I was a beginner, learning to play (about 40 years ago) - if I move this piece, then he'll move that piece, and I'll move this piece, and I'll checkmate him in two moves! This was exactly the thought process I would go through - making the best moves for me, and then guessing my opponent's next move.

It rarely worked out that way, though, when I played a real game. Instead, my actual opponent would see my plans, make a clever move of his own and capture my key piece before I got chance to move it within range of his King.

Underestimating (or, to quote a phrase, misunderestimating) my opponent's thoughts and plans is a problem that's inherent with playing skill and strategy games like Chess. In my head, my opponent can only play as well as I can.

However, when I play solo, I can make as many moves as I like, but both sides can do whatever I like, and I can win because I constructed my opponent to follow the perfect sequence of moves to let me win. And I can even fool myself into believing that I won because I had the better ideas and the best strategy.

And this is a common pitfall among Persona Designers (I've written a whole series on the pitfalls of A/B testing). They impose too much of their own character onto their persona, and suddenly they don't have a persona, they have a puppet.

"Jane Doe is clever enough to scroll through the product specifications to find the compelling content that will answer all her questions."

"Joe Bloggs is a novice in buying jewellery for his wife, so he'll like all these pretty pictures of diamonds."

"John Doe is a novice buyer who wants a new phone and needs to read all this wonderful content that we've spent months writing and crafting."

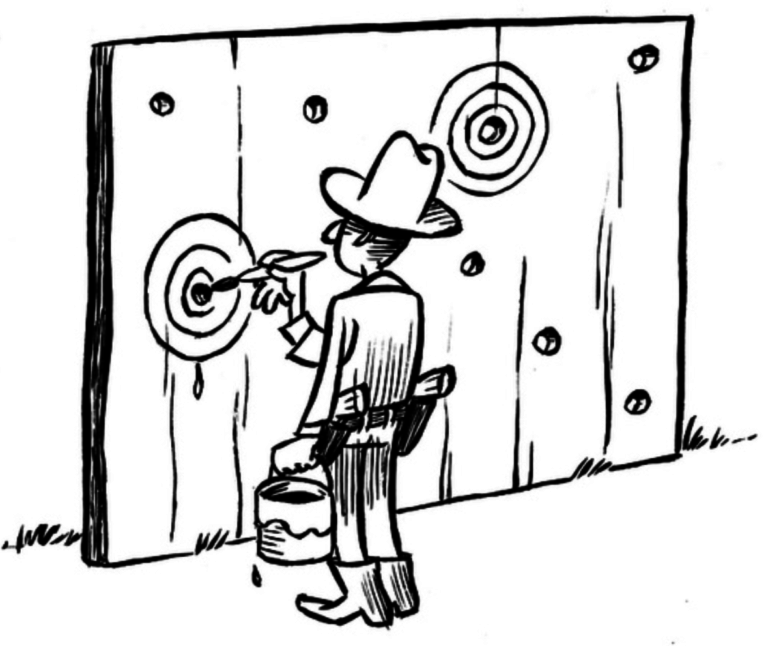

This is something similar to the Texas Sharpshooter Fallacy (shooting bullets at the side of a barn, then painting the target around them to make the bullet holes look like they hit it). That's all well and good, until you realize that the real customers who will spend real money purchasing items from our websites, have a very real target that's not determined by where we shoot our bullets. We might even know the demographics of our customers, but even that doesn't mean we know what (or how) they think. We certainly can't imbue our personas with characters and hold on to them as firmly as we do in the face of actual customer buying data that shows a different picture. So what do we do?

"When the facts change, I change my mind. What do you do, sir?"

Paul Samuelson, Economist,1915-2009